Abogados ¿Inglés fluido o falso?

¿Qué tan bueno es tu inglés? Si eres abogado con experiencia y quieres trabajar en un entorno internacional, quizás te hayas hecho esta pregunta más de una vez. Y es que el inglés es un requisito indispensable para muchos puestos de trabajo en el sector legal, y no basta con decir que lo dominas, sino que hay que demostrarlo con una certificación oficial.

[Video] Prueba tu Listening: Abogados ¿Inglés fluido o falso?

Sin embargo, según un estudio que realizamos en Work On Law, descubrimos que un número excesivo de abogados tienden a sobreestimar su nivel de inglés en su hoja de vida, lo que puede generar desconfianza y decepción entre los empleadores.

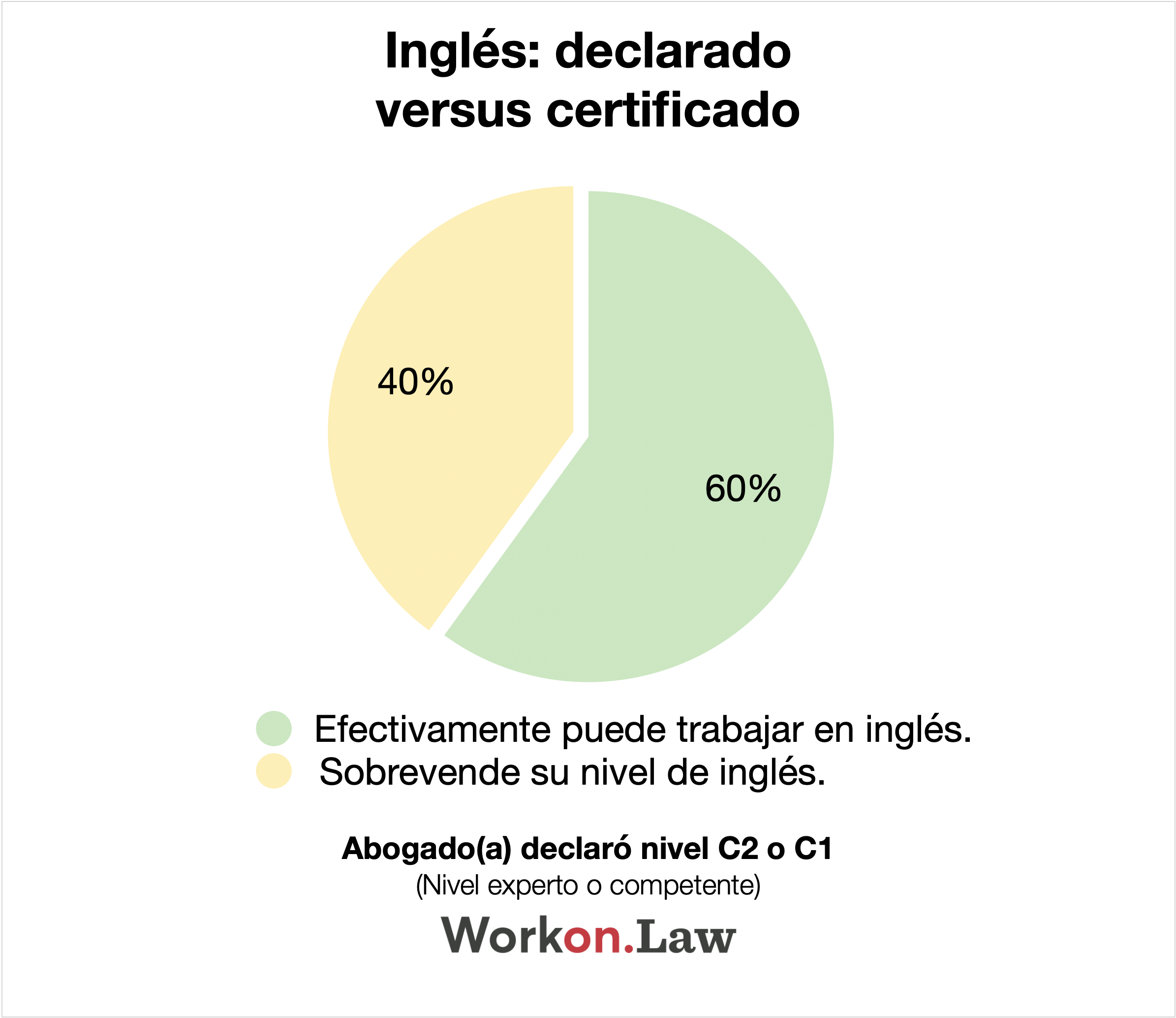

El estudio comparó el nivel de inglés declarado por los abogados con el que obtuvieron en una prueba de certificación reconocida internacionalmente, como el TOEIC, el TOEFL, Duolingo o el Cambridge English. Los resultados fueron sorprendentes: solo el 60% de los que afirmaron tener un nivel C1 o C2, es decir, ser usuarios competentes o expertos, pudieron respaldar su afirmación con una certificación acorde.

El 40% restante, que aseguró poder trabajar sin problemas en inglés, resultó tener un nivel inferior al que declaró, lo que implica que está vendiendo su inglés por encima de lo que realmente sabe.

El estudio también reveló que hay una diferencia de género en este fenómeno: el 70% de los que inflaron su nivel de inglés son hombres, lo que podría indicar una mayor confianza o una menor conciencia de sus limitaciones.

De acuerdo al estudio realizado por Work On Law, un 40% de los abogados que declaran ser bilingües sobrevenden su nivel de inglés.

Una situación alarmante

Esta situación es preocupante, porque hace que los empleadores pierdan credibilidad en cómo los abogados califican su idioma. Al ser tan grande el grupo de estas personas que se sobrevenden con su nivel de inglés, afirmar tener inglés avanzado hoy día es un significante vacío. Esto genera un problema para los que realmente dominan el idioma y su afirmación es cuestionada por la baja credibilidad que tiene la mera afirmación. Entonces empieza el problema de tener que recurrir a otras secciones del currículum para saber si el inglés que afirma tener tiene sustento en la realidad, por ejemplo porque ha vivido fuera del país, porque estudió en alguna institución, y lo que es peor, promueve la odiosa práctica de preguntar dónde estudió enseñanza básica y media, esperando que la respuesta se menciona algún colegio británico por ejemplo.

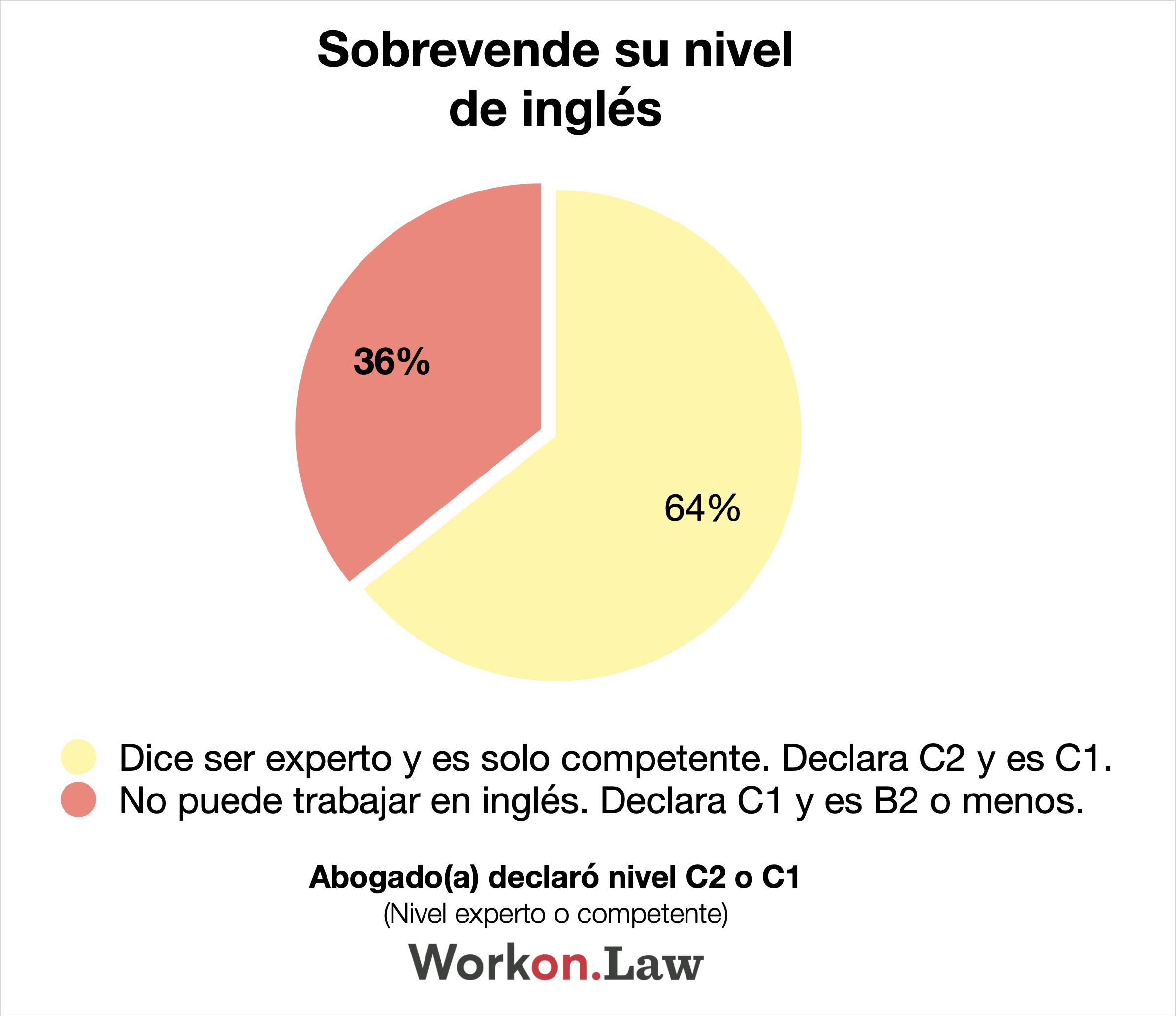

Lo más alarmante es que, dentro del grupo que sobrevende su inglés, un tercio ni siquiera puede trabajar fluidamente en inglés, porque obtiene un B2 o menos, según mostramos en el gráfico. El nivel B2, según el Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las Lenguas, corresponde a usuarios independientes del idioma, que pueden entender las ideas principales de textos complejos, pero que carecen de la fluidez y la precisión necesarias para comunicarse con eficacia en situaciones profesionales.

Por eso, desde Work On Law recomendamos a los abogados que quieran mejorar sus oportunidades laborales que sean honestos con su nivel de inglés y que se preparen adecuadamente para obtener una certificación que lo acredite. Así, podrán demostrar su competencia lingüística de forma objetiva y fiable, y evitarán frustraciones y malentendidos tanto para ellos como para sus potenciales empleadores.

Radiografía de la sobreventa de los abogados y su nivel de inglés: no son tan expertos ni competentes como declaran.

Aprender y manejar el inglés es una de las habilidades más útiles para todos los abogados por lo que mantener y probar el nivel del idioma se ha vuelto tan importante.

¿Cuánto permanecer en mi primer trabajo?

¿Cuánto durar en tu primer trabajo?

La permanencia en tu primera experiencia laboral es un dato que potenciales empleadores ocupan para filtrar tu CV.

Tu futuro jefe(a), cuando revise tu CV esperará que hayas permanecido en tu primer trabajo lo mismo que ellos duraron. Para entregarte el dato preciso, en Work On Law analizamos la trayectoria laboral de 120 gerentes legales en Chile, 60 Generación X y 60 Millennials*.

Duración de actuales Chief Legal Officers (“Gerente Legal” o “Fiscal”) en su primer trabajo como abogado(a):

Generación X (1965 – 1980)

– Promedio: 8 años

– Mediana: 4 años

– Moda: 2 años

Millennials (1981 – 1996)

– Promedio: 4 años

– Mediana: 3 años

– Moda: 2 años

[* Estudio realizado por Work On Law en diciembre de 2023, tomando una muestra de 120 abogados en Chile]

La moda estadística (el valor que más se repite en un conjunto de datos) en ambos casos es 2 años. Por lo tanto lo más probable es que tu futuro jefe(a) espere que hayas durado 2 años en tu primer trabajo.

Cuánto sube el sueldo de un abogado sí estudia un LL.M en Estados Unidos

Revisa aquí la entrevista de Las Ultimas Noticias al CEO de Work On Law. Obtener un LL.M esta cambiando de forma radical no solo las oportunidades de los abogados sino también sus sueldos, cada vez más abogados deciden estudiar un Master en Leyes internacionalmente para destacar de su competición.

Ver nota de prensa de Oscar Valenzuela en Las Ultimas Noticias, 1 de noviembre de 2022.

Si tienes dificultad para leer la nota, hacer click en este enlace: Cuánto sube el sueldo de un abogado si toma un magister en EE.UU

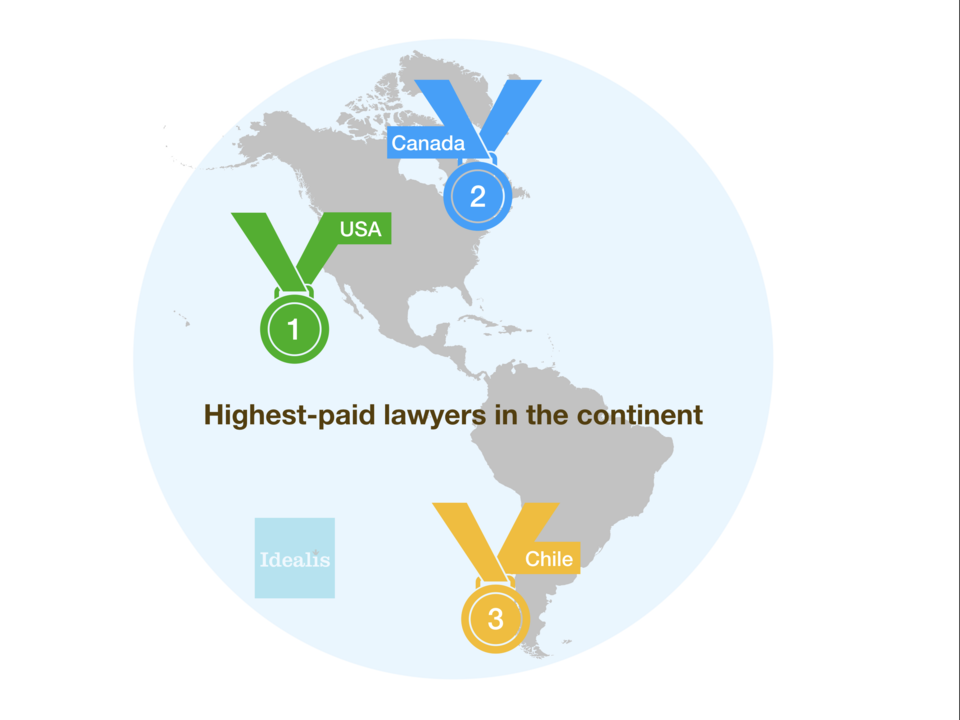

Highest-paid lawyers in the continent

According to our data, on average Chilean lawyers are likely to be better compensated than their peers in the rest of the continent (with the only exception of those qualified in the United States and Canada).

It comes as no surprise that US lawyers, followed by Canadians, have the highest total compensation in the continent. However, Chile holds a solid third place. This might shock those who expect the bronze would go to countries with much larger populations, such as Mexico, Brazil, Perú or Colombia.

Chilean Lawyers: the best paid in Latin America

Chile is definitely a powerhouse in the region. Solid institutions have attracted global companies for decades. The nation’s capital, Santiago, has climbed in the ranks of expensive cities and is home to elite practitioners who have completed an LL.M from a top foreign law school, an internship at an American law firm and/or admission to the NY Bar.

Senior Associates of top tier law firms in Chile will have pocketed around USD 120,000 this 2018. Such firms can easily put USD 43,000 per annum in the hands of entry-level lawyers in their early twenties.

A last token of this trend is the ever-growing segment of young General Counsels that have surpassed the USD 420,000 threshold (salary + bonuses); and some of them are not even in regional roles.

English is mandatory to land any of these high-paying jobs. However, soft skills is the critical trait of this new generation of highly sophisticated attorneys.

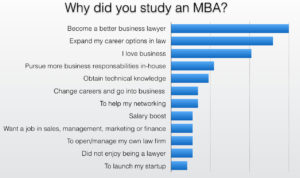

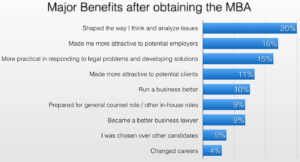

Lawyers, do you really need an MBA?

It won’t earn you more money, but for sure, it will shape the way you think.

At least that’s what the majority of those who hold an MBA’s we’ve surveyed have responded.

Every year there’s a new MBA ranking, but some Business Schools are opting out to provide their info to the magazines that publish them. I think an unsaid reason for those schools to abstain is that it’s hard to make any sense out of the fact that one year you may be at the top of the ranking and the next be ranked several places down, just because the ranking has now included a new criterion.

Therefore, rather than offering yet another ranking, here are the most powerful motivations behind the growing number of lawyers who are willing to spend considerable resources in pursuing this still unique accolade for their resume. Unique because around 4% of lawyers in pan-Canadian law firms have an MBA. Take Stikeman Elliott for example: 6%.

Our respondents also tell us how they have benefited from having an MBA, sending a positive signal to those who are thinking about getting one. However, they raise two important red flags on what to expect: there's no guarantee that having an MBA will land you a better job, nor that you'll earn more money.

We asked 150 JD/LLB + MBA in Canada; these are their answers:

Finally, here are some quotes from our respondents:

An MBA adds immediate credibility for a business lawyer.

I think the biggest thing is really that there are no guarantees. If you have a good law school average and you would be competitive anyways, an MBA makes you really stand out. If you have a poor law school academic record, the MBA won't save you. And yes, the program is a LOT of work. I don't regret it for a second though and I'm quite sure the great legal job I have lined up for after law school is at least partly attributable to my JD/MBA.

I highly recommend an MBA, especially for those lawyers that don't have a business background. Private practice is a business and most lawyers don't have the business skills to run a business. Further many areas of law beyond corporate/commercial have a financial component, for example family law can have a complicated financial component that I notice many lawyers don't fully understand.

Another reason to pursue a joint Masters degree (of any kind) is that it opens the door to graduate student funding opportunities - many JD/MBA students are able to subsidize their law degree using government or grad school funding that is not available to JDs (considered an undergraduate program for most purposes).

Law Schools that will land you a job on Bay Street

Maclean’s Magazine compares law schools every year. Osgoode Hall has routinely ranked in the bottom third* when it comes to “elite firm hiring”, one of the several aspects the Magazine considers to determine “graduate quality”. It is an interesting study, but it doesn't seem to portray the fact that 22% of the lawyers that currently work with one of the “Seven Sisters” studied law at Osgoode, putting the school in first place, even ahead of U of T (21%).

Alma mater, matters! The best Law Schools are a direct conduit to the best law firms

Let’s focus on one single stat: which law schools can claim a greater percentage of their graduates employed in Canada’s biggest law firms? But first of all, why consider only Big Law? Although talented lawyers can be found in smaller firms, public service, universities and companies, large law firms have tailor-made selection processes intended to secure the best articling students. Later on, they’ll apply rigorous filters to verify reputation and the portability of a lateral’s practice.

Here are the stats we obtained after crunching the data of nearly 4,000 Big Law lawyers nationwide. Use the first year enrolment charts to help you gauge the size of each faculty.

Law schools that will land you a job on Bay Street

If you’re bound for Bay Street, the chart below will help you see what those firms are made of:

When considering the amount of students of each faculty, U of T graduates seem to be the most successful in getting hired by Big Law all across Canada.

As to the “Seven Sisters”, more than half of the partners and associates went to Osgoode Hall or U of T. Next time we will have a closer look at the Sister's numbers.

* Osgoode ranked 10 out of 16 in the “Elite Firm Hiring” section of the 2013 edition; up from nº12, in the 2009 edition. ** First year enrolment information was obtained from oxfordseminars.ca. The number for University of Montreal was approximated by the author.

Multi-Bar Lawyers in Canada

Are you admitted to practice law in multiple jurisdictions?

If so, you might be among the 12.1% of Canadian lawyers working at large firms who can flash more than one badge to appear in court. If you think that the most common combination is to be admitted to practice both in Québec and in Ontario, you might have to guess again. Oddly enough, 31% of “multi-bar lawyers” in Canada are allowed to practice in the state of New York.

We analyzed the profiles of 3,142 lawyers who currently work in Canada’s largest law firms

We analyzed the profiles of 3,142 lawyers who currently work in Canada’s largest law firms and surveyed quite a few partners and lawyers from such firms.

Under national mobility agreements many lawyers are allowed a limited practice in other provinces; however, only those that are called have no restrictions when representing their clients’ interests.

This article, when stating a lawyer is admitted to practice refers to those that are fully licensed.

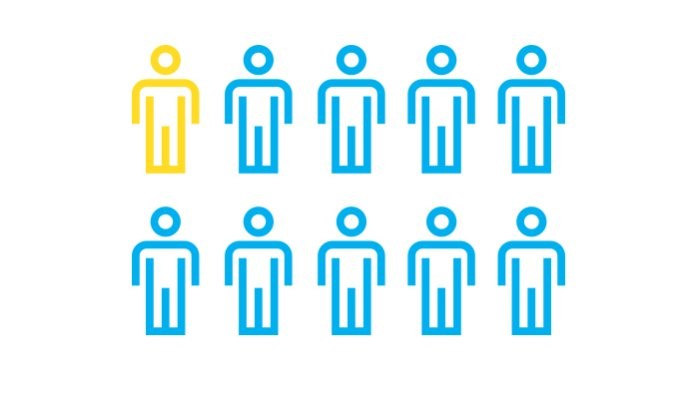

Roughly, only 1 out of 10 lawyers who work in these big and competitive law firms can practice in more than 1 jurisdiction. Is this an asset to these already top-notch lawyers? Absolutely, it sets them apart from the crowd:

· 12.1% of these multi-bar lawyers have been called to more than 1 bar

· 1.6% have been called to 3 bars

· 0.2% have been called to 4 or more

How unique is your combination?

A compelling law-firm bio reads: “Jane Roe is one very few lawyers whose call to both the Quebec and Ontario Bars qualifies her as a ‘national’ practitioner”. Jane Roe is among the 12.8% multi-bar lawyers who combine ON & QC bars. Other common combinations are:

· AB & ON: 16.8%

· BC & ON: 16.5%

· Any province & any territory: 9.0%

· BC & AB: 8.8%

However, the most common combination for a lawyer in Canada actually does not involve any of the Canadian provinces or territories, but rather the State of New York:

· Canadian bar & NY: 31.1%

· ON & NY: 21.5%

“It has been useful to my practice”

Many multi-bar lawyers could argue that, in their case, this was a result of having had to update their credentials upon moving to another province or territory.

But what about the increasing number of lawyers being admitted to practice in the Territories? Why are most lawyers with more than 3 calls to different bars specialized in litigation, environmental law or aboriginal law? Or why would someone in the area of capital markets be admitted to all Prairies and the Yukon?

For many it has been a strategic decision.

Litigation attorney Keith Marlowe, an associate at Blakes, is among the 0.06% of lawyers in Canada who can actually appear before courts in more than 6 jurisdictions both in the US and Canada. He uses his Alberta and Ontario bar calls on a daily basis. His multiple-bars have helped him to speak the technical language required in each jurisdiction. For example, Alberta has adopted the term “questionings for discovery”, whereas other provinces use “examinations”; in the US the proper term is “depositions”. England and Wales have their own jargon that is familiar to him as well, because in fact, he is admitted to practice there too. 8% of Canada’s multi-bar lawyers have been called to the Bar of England and Wales.

Maxime Faille is a partner in Gowlings' Ottawa Aboriginal Law and Litigation Group. He has been called to the NWT, Yukon, and Ontario bars, and has an impending call to the Nunavut bar. In his words: “the northern jurisdictions do not participate in mobility and, as such, an ability to practice law on behalf of clients there is quite limited.” Multi-bar membership has been essential to his engagement in constitutional litigation in the territories and incidentally helpful to his practice in Aboriginal law, where he deems that having multiple bar calls is increasingly the norm and something necessary.

Mathew Good, a Vancouver associate of Blakes’ litigation group claims that his 5 bar admissions, quite a record, have helped him comply with the Inter-Provincial Mobility Agreement that sets practice limits on lawyers who haven't been called to the relevant bar. Matthew points out that these admissions to multiple-bars “have been beneficial to my practice, because they have given me – through examinations and admission – deeper familiarity with jurisdictions in which I regularly practice, as well as respect and connection with members of those Law Societies.”

Bill McNaughton, a partner at BLG is licensed to practice in BC, Alberta and Yukon. This has been especially useful to his practice in TeamNorth®, a section of BLG servicing Nunavut, Northwest Territories, Yukon and the upper regions of several provinces.

Patrick Floyd is a partner at Gowlings Ottawa office. He has been called to the New York, Ontario and Nunavut bars. This has not been due to him moving from one place to the other, but rather an asset to his practice in aviation. His combination is actually an excellent blend of Canadian provinces and Territories and the US.